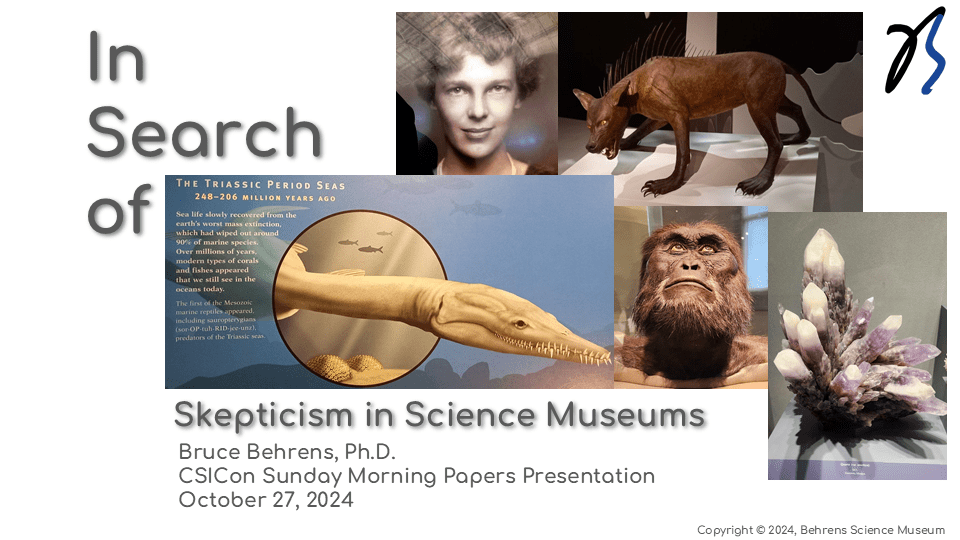

Why should we care about skepticism in science museums? Skepticism is central to the process of science, and science museums are an important public face of science. Therefore, I think science museums should discuss not only the products of science but the process of science. Pseudoscience and the paranormal are great topics to use to teach the process of science.

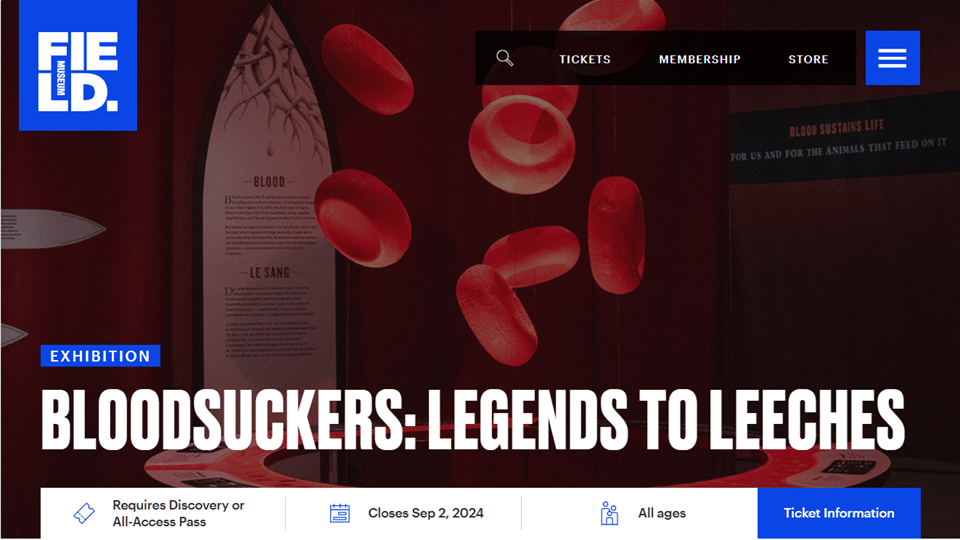

I began my presentation with an anecdote. In March, 2024, my family and I visited Chicago for spring break, and one of the places we visited was the Field Museum of Natural History. One of the exhibitions at the Field Museum was called, “Bloodsuckers: Legends to Leeches.”

The “Bloodsuckers” exhibition discussed a wide variety of creatures, including mosquitoes, biting flies, leeches, vampire bats, and even a snail that sucks blood from fish. The exhibition also discussed bloodletting, humoral theory, and the history of barbers. And it discussed legends, including vampires in history and popular culture.

And it had a Chupacabra exhibit.

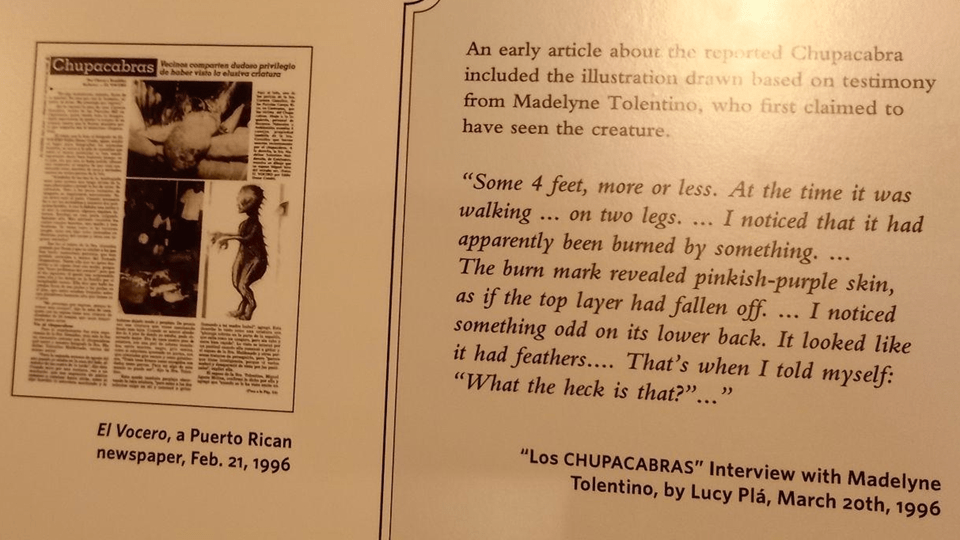

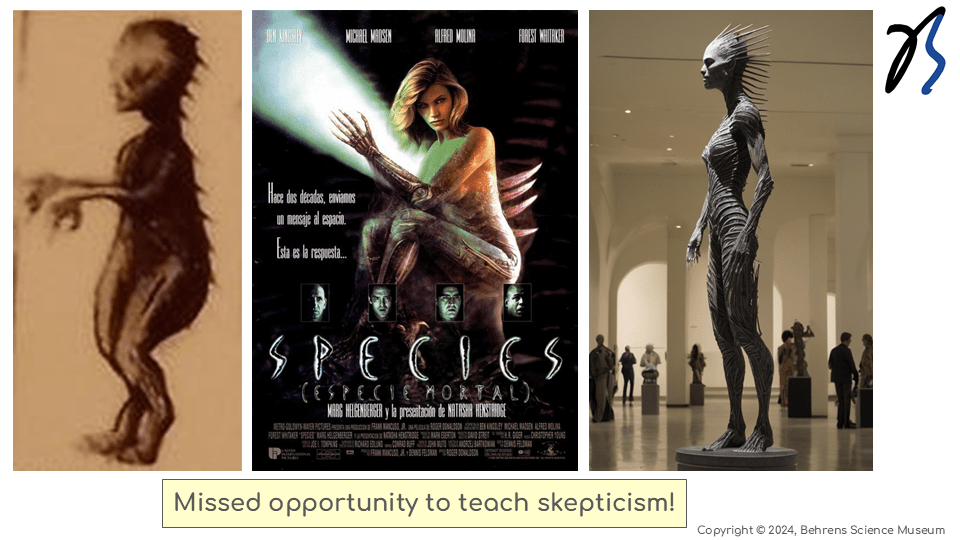

The exhibit included a panel showing a newspaper with a sketch of the chupacabra based on the eyewitness report of Madelyne Tolentino, the woman who first claimed to have seen the creature.

In addition to the exhibit panel with the newspaper, there was also a model of a chupacabra.

The exhibit panel for the model states:

In Puerto Rico in 1995, residents found farm animals drained of blood. With no apparent explanation for such a terrifying loss of livestock, a report blamed a newly-conceived creature called El Chupacabra (literally “goat sucker” in Spanish.) The creature was described and illustrated on the front page of a newspaper and the stories spread. Alleged sightings occurred across the nation and into Mexico and the Southern United States. Since then, hysteria has spread and the bloodsucking Chupacabra is now depicted in both fantastical and frightening ways, quite different from its original description.

The point of the exhibit is that over time the appearance of the chupacabra has evolved, suggesting that the chupacabra is not real, although the exhibit doesn’t state this explicitly.

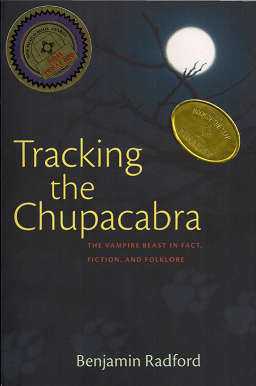

Another thing that the exhibit doesn’t mention is that in 2011, Benjamin Radford published the book, Tracking the Chupacabra. In his book, Radford highlighted numerous similarities between Ms. Tolentino’s description of the chupacabra and the appearance of the human-alien hybrid creature depicted in the (fictional!) movie Species.

The movie Species came out in 1995, and Ms. Tolentino had seen it just a few weeks before her sighting of the chupacabra. It’s disappointing that the exhibit did not include this information, because it’s a missed opportunity to teach skepticism. The exhibit could have featured a model of the creature from the movie (the slide shows an AI-generated exhibit that only slightly resembles the movie creature) and explained how our minds tend to fill in the blanks when confronted with limited information. This phenomenon, known as pareidolia, causes us to perceive familiar patterns—such as faces or creatures—in ambiguous stimuli. By linking Tolentino’s recent viewing of Species with her chupacabra sighting, the exhibit could have discussed how our observations can be influenced by our expectations.

Are science museums skeptical?

How can we address this question? What do the data say?

My original plan to address the question was to do “content analysis” on museum exhibits. “Content analysis” is a term of art in the fields of textual data analysis, communications, media studies, and social sciences. It refers to the systematic, objective, and quantitative analysis of the content of written, verbal, or visual communication.

The analysis would include three parts: first visit a large number of science museums. Second photograph as many of the exhibit panels as possible. Third assess each exhibit panel as either factual, skeptical, or uncritical/credulous.

The problem with this method is that it’s a lot of work. I took almost 600 photographs at the National Museum of Natural History. Each exhibit panel includes about 100 words, so that’s 60,000 words to read and assess. That’s about one third of a book like The Skeptics Guide to the Universe. So I modified my plan.

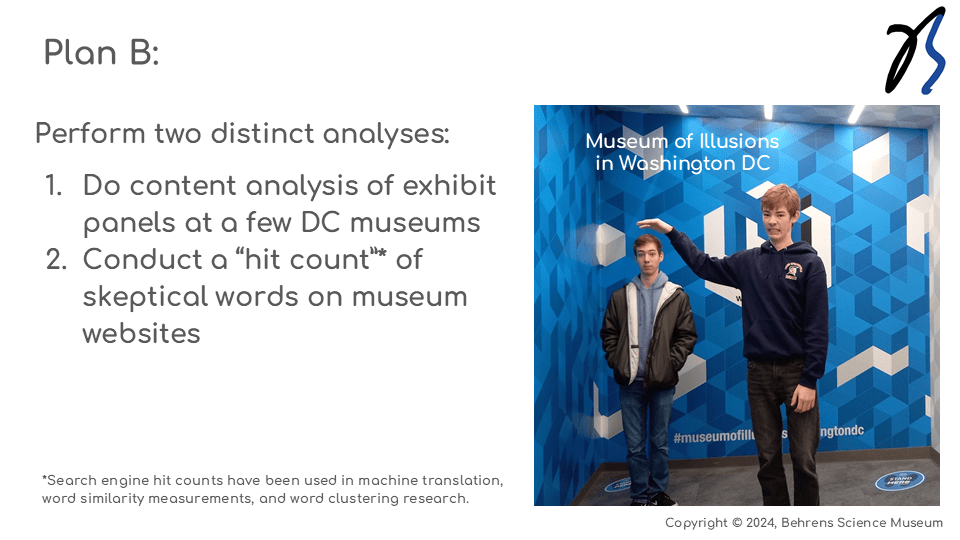

My “plan B” was to do the content analysis, but on a smaller number of museums, primarily museums in the Washington DC area. That analysis would be augmented with a second analysis that would do a “hit count” of skeptical words on museum websites. “Hit count” is a term of art in the fields of information retrieval, search engine optimization, library and information science, data science, text mining, and web analytics.

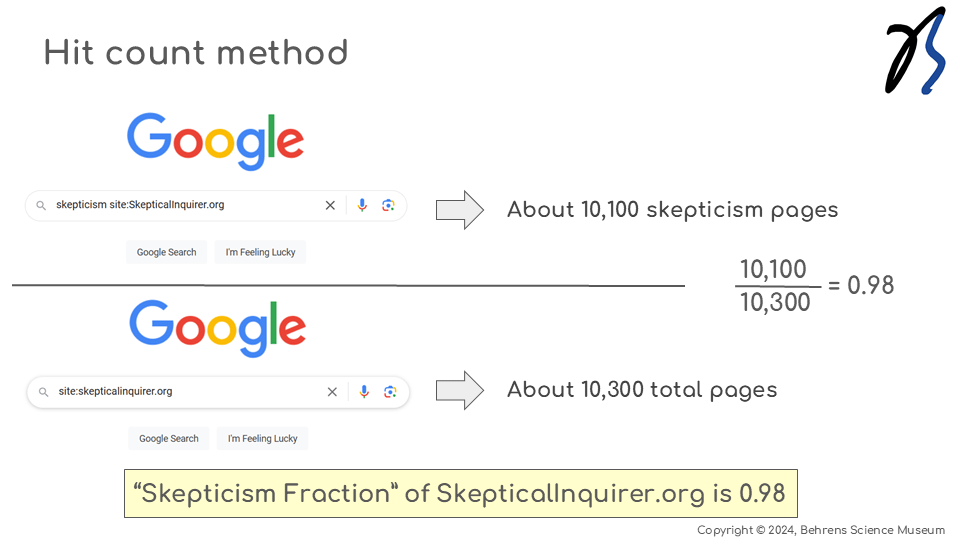

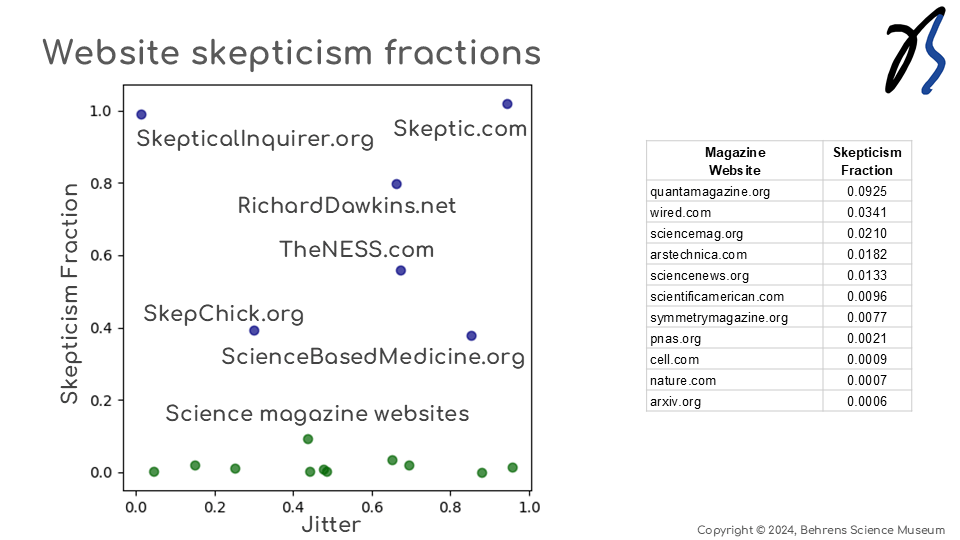

Using the “site:” key word in a Google search restricts the search to that website. A Google search for “site:SkepticalInquirer.org” provides an estimate of the total number of pages on the Skeptical Inquirer website. Adding the word “skepticism” to the search (without quotes, as shown in the slide) gives an estimate of the number of pages on the website that include the word “skepticism,” “skeptical,” “skeptic,” etc. Since the word “skeptical” is in the name of the website, essentially all of the pages match the search (0.98 for SkepticalInquirer.org). I define the “skepticism fraction” of a website as the fraction of pages that include the word “skepticism” or related terms (as defined by Google). In previous iterations of this presentation, I used a more complicated query (see my presentation to NCAS here), but this new query is easier to explain and seems to work just as well.

This fraction can be calculated for any website. In the figure below, the skepticism fraction is shown on the vertical axis. The horizontal axis is just noise to spread the data points out so that they are easier to see. Websites with “skeptic” or “skeptical” in the name are close to 1.0, but other skeptical websites also have relatively large skepticism fractions.

What about the websites of science magazines?

The figure shows that science magazine websites typically have low skepticism fractions. Quanta Magazine website had the highest skepticism fraction at 0.09, with most magazine websites being close to zero.

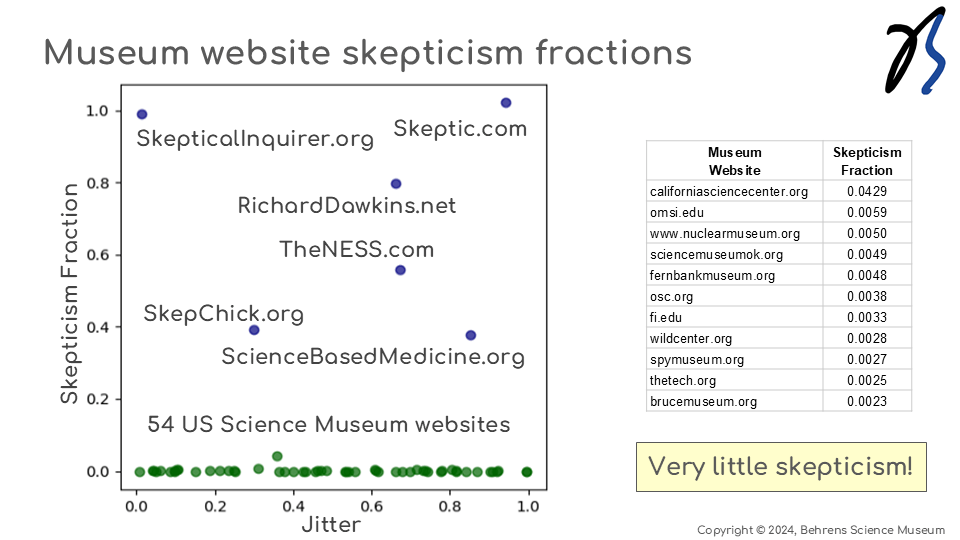

And what about science museum websites?

Of the 54 science museum websites that I included in this analysis, the California Science Center had the highest skepticism fraction at 0.04. This was due largely to a few blog posts related to COVID-19 and anti-vaccination misinformation (Run the query yourself).

My conclusion is that there is very little skepticism present on science museum websites.

Going back to the content analysis of museum exhibit panels, I realized that artificial intelligence could help with the analysis.

My new plan was to do the content analysis using OpenAI GPT-4o (ChatGPT, but using the application programming interface, API). I visited five different museums (so far), took as many photographs as I could, and then used GPT-4o to process them. I analyzed the data in two steps. First, I had GPT-4o transcribe the text in the photos. Then, separately, I had GPT-4o assess the text of each exhibit panel according to a rubric and categorize each panel as either factual, skeptical, or uncritical/credulous. I double checked the results for a subset of the data using a second rubric (both are provided at the end of this post). I also manually spot-checked the results.

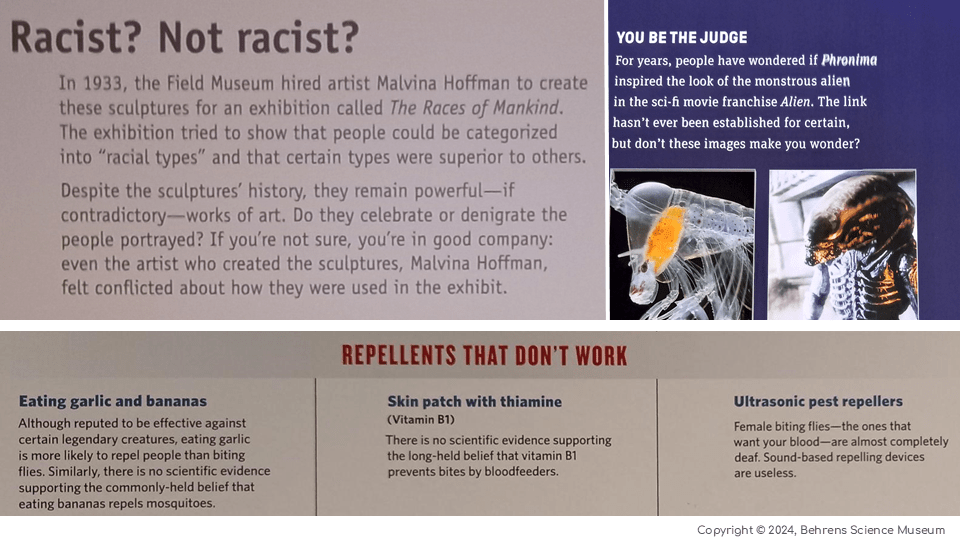

Uncritical/Credulous Exhibit Panel Examples

Among the exhibit panels that GPT-4o assessed as uncritical/credulous were the two panels on the chupacabra. GPT-4o explained its reasoning as follows:

This panel heavily leans on the sensational and speculative language associated with the Chupacabra myth. It emphasizes the mysterious nature of the creature and its alleged sightings without scrutinizing or questioning the validity of these claims. The panel also includes an unverified personal account that adds to the mythical portrayal of the Chupacabra. There is no mention of scientific evidence or skepticism, thus it fits the Uncritical/Credulous category.

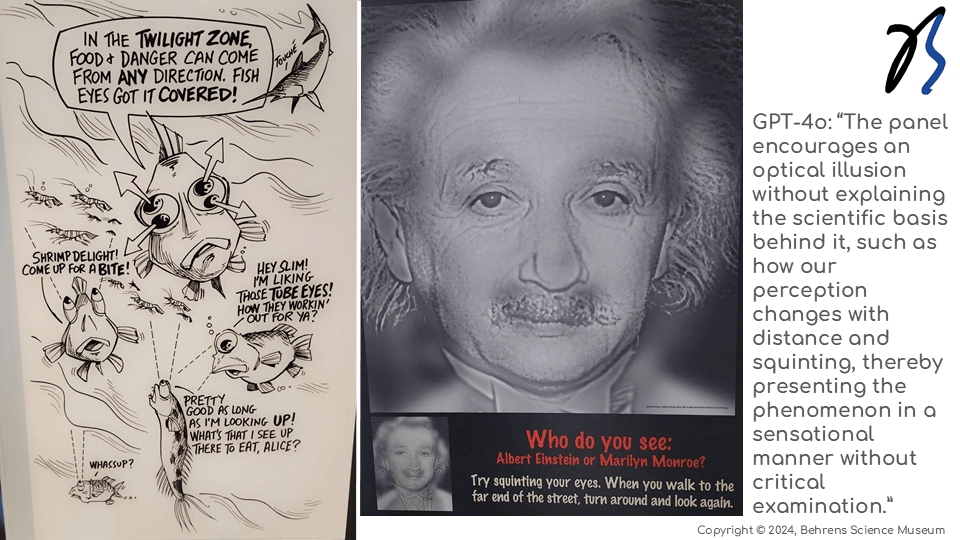

The fish cartoon is another example of an exhibit panel that was identified as uncritical/credulous. The cartoon anthropomorphizes the fish living in the “Twilight Zone” (not so deep that it is always dark, but deep enough that it is never very bright).

Optical illusions like the Einstein/Marilyn Monroe illusion on the right are common in science museums. GPT-4o noted that “the panel encourages an optical illusion without explaining the scientific basis behind it…” Museum exhibits often present optical illusions as uncommon and surprising. In reality, our minds are constantly playing tricks on us. What’s truly remarkable about optical illusions is that we realize that our minds are deceiving us!

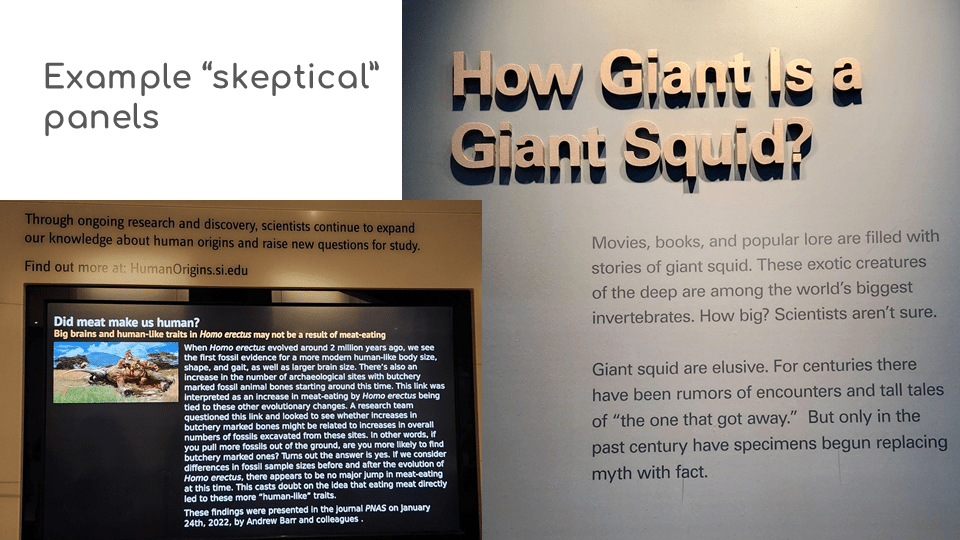

Skeptical Exhibit Panel Examples

Next, are some examples of exhibit panels identified as skeptical. The first panel has to do with scientists changing their minds based on new information. This is an example of skepticism and the process of science, although not related to pseudoscience or the paranormal.

The second panel is about the Giant Squid, which is not a cryptid, it’s a real creature. It does talk about “replacing myth with fact,” but its connection with scientific skepticism is weak.

The “Racist? Not racist?” panel asks whether sculptures created for a racist exhibit in the 1930s are racist themselves. GPT-4o asserts that this discussion encourages critical thinking. Likewise, for the panel that asks whether the aquatic parasite Phronima inspired the alien in the movie Alien.

The last exhibit panel labeled as skeptical states that eating garlic does not repel biting flies and that eating bananas does not repel mosquitoes. This panel is certainly skeptical and aligns with a broader skepticism regarding alternative medicine.

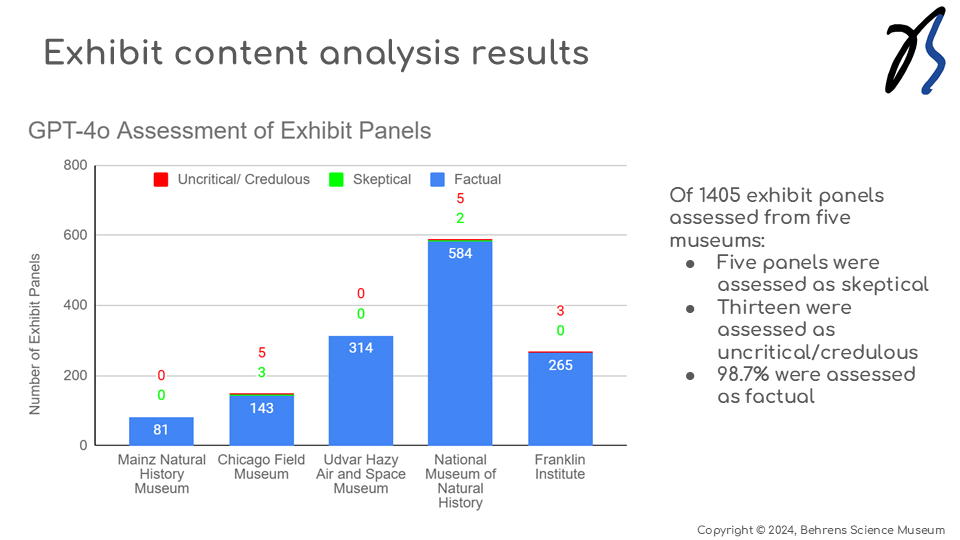

The result of the content analysis is shown below. I visited five museums, the Mainz Natural History Museum, the Chicago Field Museum, the Udvar Hazy Air and Space Museum, the National Museum of Natural History, and the Franklin Institute. Of the 1405 exhibit panels assessed, only five (all shown above) were assessed as skeptical, while thirteen exhibit panels were assessed as uncritical/credulous. Almost 99 percent were assessed as factual.

In summary, the science museums that I visited included essentially no skeptical content. Uncritical/credulous exhibit panels were more common than skeptical panels, and none of the 54 museum websites analyzed suggested skeptical museum content.

So, I founded the Behrens Science Museum. Ok, actually I founded the museum first. I realized that I should test the hypothesis that science museums aren’t skeptical when I decided to apply to speak at CSICon.

The vision for the Behrens Science Museum is to create a museum of science and skepticism that teaches critical thinking and the scientific method through exhibits about pseudoscience and the paranormal.

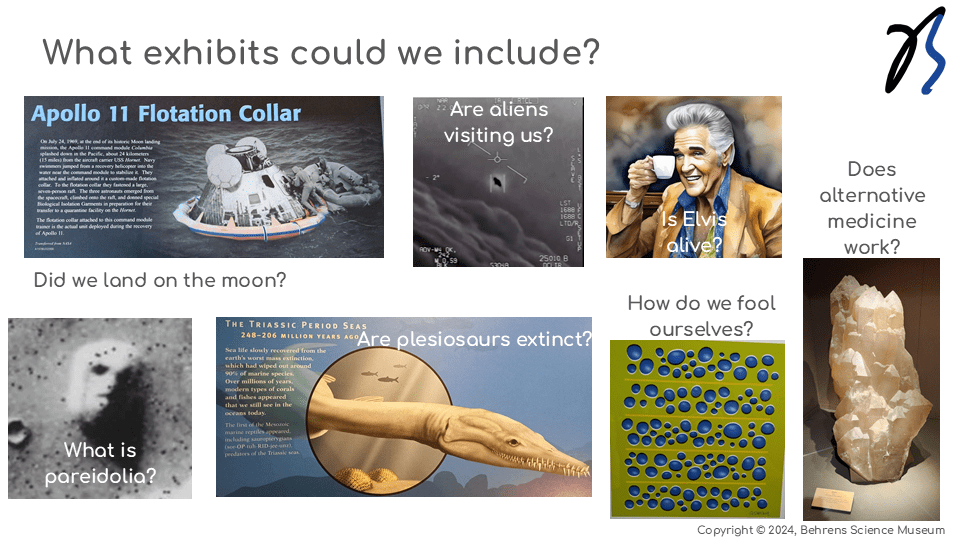

The museum might include exhibits about ghosts, ESP, astrology, homeopathy, chiropractic, acupuncture, moon landing hoax, flat Earth, chemtrails, cryptozoology, anti-vaccine, UFOs, alien abductions, remote viewing, and conspiracy theories, like the “moon landing hoax.”

Exhibits could be composed of paintings, drawings, sculptures, crystals, LEGO® models, 3D-prints, photos, music, poetry, comics, videos, simulations, and other art. Performances, cooking or baking may also occur.

Together we can build this museum! But we need your help! We need board members, partner organizations, and connections with like-minded individuals. Tell your friends about bsmuseum.org

We need to obtain non-profit status and increase our social media presence.

We need to develop exhibit ideas and create artwork.

And we need financial support.

The views expressed in this presentation do not necessarily reflect the views of CNA, the Center for Naval Analyses, the US Navy, or any other CNA sponsors.

Also, the intention of this briefing is not to criticize any specific museum. Every science museum has its own mission statement and board of directors. They are not necessarily focused on skepticism. If we want a skeptical science museum, we need to build it!

Thank you!

Primary Rubric

You are tasked with assessing the content of museum exhibit panels. For each panel provided, categorize the content into one of three categories: Uncritical/Credulous, Factual, or Skeptical. Use the criteria below to make your assessment.

Categories and Criteria:

- Uncritical/Credulous

Description:

The panel presents information without critical examination or evidence.

It includes or emphasizes paranormal or pseudoscientific explanations.

It uses sensational or speculative language (e.g., “mysterious,” “unexplained,” “supernatural”).

Examples:

Claims the Bermuda Triangle is responsible for Amelia Earhart’s disappearance without acknowledging the lack of evidence.

Describes UFO sightings as definitive proof of extraterrestrial life without presenting counter-evidence or skepticism.

Presents conspiracy theories or myths as credible without critical analysis. - Factual

Description:

The panel provides verifiable, evidence-based information.

It focuses on established scientific facts and widely accepted historical accounts.

It avoids speculation and sticks to documented events and data.

Examples:

Describes the documented events surrounding Amelia Earhart’s disappearance without delving into unproven theories.

Provides information about space missions based on official reports and scientific research.

Explains natural phenomena like earthquakes or eclipses using established scientific principles. - Skeptical

Description:

The panel critically examines claims, especially those related to pseudoscience or the paranormal.

It provides context by presenting multiple viewpoints and highlighting the lack of evidence for unproven theories.

It encourages critical thinking and scientific skepticism.

Examples:

Discusses the theories surrounding Amelia Earhart’s disappearance, including the Bermuda Triangle, and emphasizes the lack of credible evidence for paranormal explanations.

Analyzes claims of alien encounters with a focus on scientific investigation and the importance of evidence.

Presents historical myths and legends, clearly differentiating between folklore and factual history, and encouraging visitors to question extraordinary claims.

Instructions:

For each exhibit panel text provided, categorize it into one of the three categories (Uncritical/Credulous, Factual, or Skeptical) and provide a brief explanation for your categorization. Use the criteria and examples provided to guide your assessment.

Example Assessments:

Panel Text:

“Amelia Earhart disappeared under mysterious circumstances in the Bermuda Triangle, a place known for supernatural occurrences.”

Assessment: Uncritical/Credulous

Explanation: This panel uses sensational language and emphasizes a paranormal explanation without acknowledging the lack of evidence.

Panel Text:

“Amelia Earhart disappeared during her flight in 1937. Despite extensive searches, her plane was never found, and the exact cause of her disappearance remains unknown.”

Assessment: Factual

Explanation: This panel provides a straightforward, evidence-based account of the event without delving into unproven theories.

Panel Text:

“Amelia Earhart disappeared while flying over the Pacific Ocean. Although some have suggested paranormal explanations like the Bermuda Triangle, there is no scientific evidence supporting these claims. Most experts believe she ran out of fuel and crashed into the ocean.”

Assessment: Skeptical

Explanation: This panel presents multiple viewpoints, highlights the lack of evidence for paranormal explanations, and encourages critical thinking.

Use this structure to ensure consistent and accurate assessments of museum exhibit panels.

Secondary Rubric

You are tasked with assessing the content of museum exhibit panels. For each panel provided, categorize the content into one of three categories: Uncritical/Credulous, Factual, or Skeptical. Use the criteria below to make your assessment.

- Uncritical/Credulous

Description: Carl Sagan would describe this category as a failure to apply skepticism or the scientific method. It presents information with a lack of scrutiny, often promoting pseudoscientific or paranormal ideas without demanding proof. In this category, the panel prioritizes sensation over substance and fails to question extraordinary claims.

Carl Sagan’s Lens:

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” These panels make remarkable assertions but do not back them up with credible or verifiable data.

They appeal to mystery and the unknown rather than science, reflecting a tendency to accept claims without the burden of evidence.

Examples:

Promoting myths like UFOs as undeniable fact without referencing credible research or counter-evidence.

Asserting paranormal causes (e.g., Bermuda Triangle) for unexplained events without a serious inquiry into more likely explanations.

- Factual

Description: Panels in this category would align with Carl Sagan’s respect for science and empirical data. They rely on evidence-based, peer-reviewed information, sticking to established facts and logical reasoning. These panels avoid the allure of the speculative and present clear, well-documented information.

Carl Sagan’s Lens:

“Science is a way of thinking much more than it is a body of knowledge.” The information presented here is grounded in evidence and logical thinking, avoiding embellishment or unsubstantiated claims.

Facts are conveyed without exaggeration or distortion, and conclusions are based on what is known rather than what is speculated.

Examples:

Documenting historical events with well-supported evidence and avoiding sensationalism.

Discussing scientific discoveries with respect to the processes that led to those findings, rather than inflating their significance or mystery.

- Skeptical

Description: Carl Sagan would appreciate panels in this category for their embrace of critical thinking and inquiry. They encourage visitors to question claims, especially those lacking evidence, and promote the scientific method as the best tool for understanding the world. These panels expose weak or baseless claims while fostering curiosity and skepticism.

Carl Sagan’s Lens:

“The beauty of a living thing is not the atoms that go into it, but the way those atoms are put together.” These panels dissect claims and theories, analyzing them with scientific rigor. They do not dismiss unproven ideas outright but demand convincing evidence before accepting them.

This category respects the importance of questioning everything, particularly when an explanation seems too neat or too extraordinary without justification.

Examples:

Acknowledging popular myths or pseudoscientific beliefs while highlighting their lack of evidence and encouraging further investigation.

Offering balanced perspectives on controversial theories, carefully weighing them against the best available evidence, and refraining from jumping to conclusions.